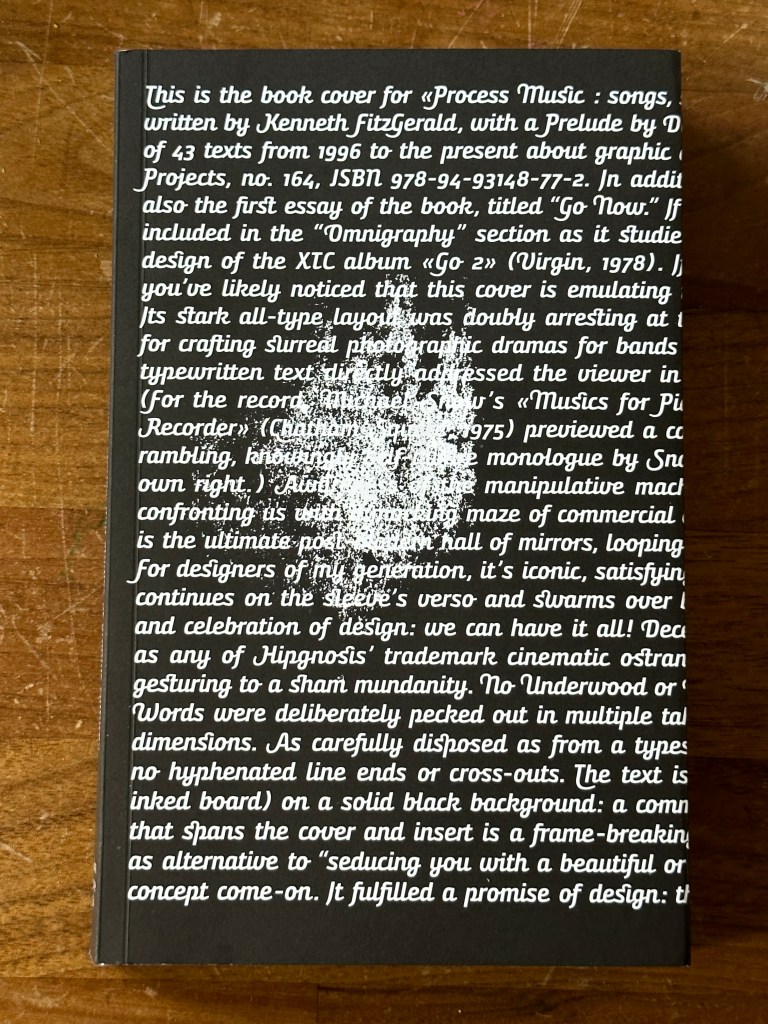

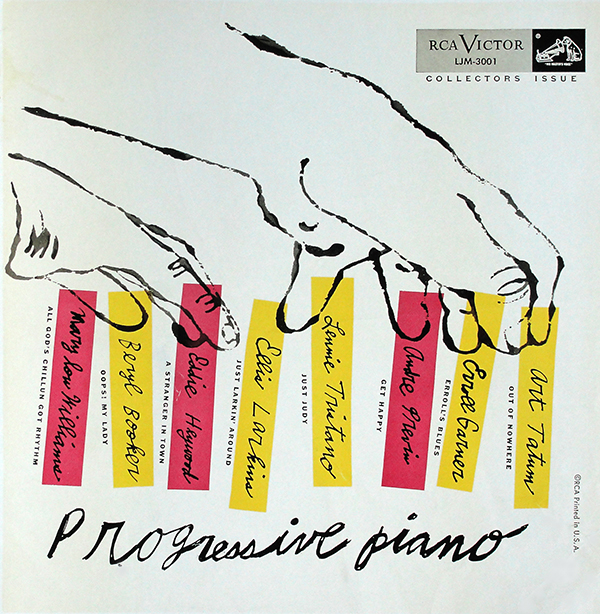

I consider myself to be a graphic designer as opposed to an artist. And as a collector of record cover art I quite ofren remake a rare cover or create covers for records that never existed, but for which cover art exists. Examples are my creation of covers for a proposed RCA Victor jazz album entitled Progressive Piano that was scheduled for release some time in the 1950s but, despite being allocated a catalogue number, was never actually released. The Warhol Museum has lithographs of Andy Warhol’s proposed designs for the covers of a 10-inch and a 7-inch version of the record. I created full-sized covers from photos of these lithographs and even made record labels to look like fifites RCA Victor labels.

Warhol also made collages for a projected Billie Holiday album to be called Volume 3. He made four versions and pictures have circulated on the Internet , so I decided to make actual covers and include records suggesting that the album would have been released by COlumbia records, though Warhol’s designs do not include a record label or catalogue number.

I consider these to be appropriations of Warhol’s art not dissimilar to those made by Elaine Sturtevant (1924-2014) who painted versions of Warhol’s Flower paintings — wnd was even given a silkscreen by Warhol to make further prints!

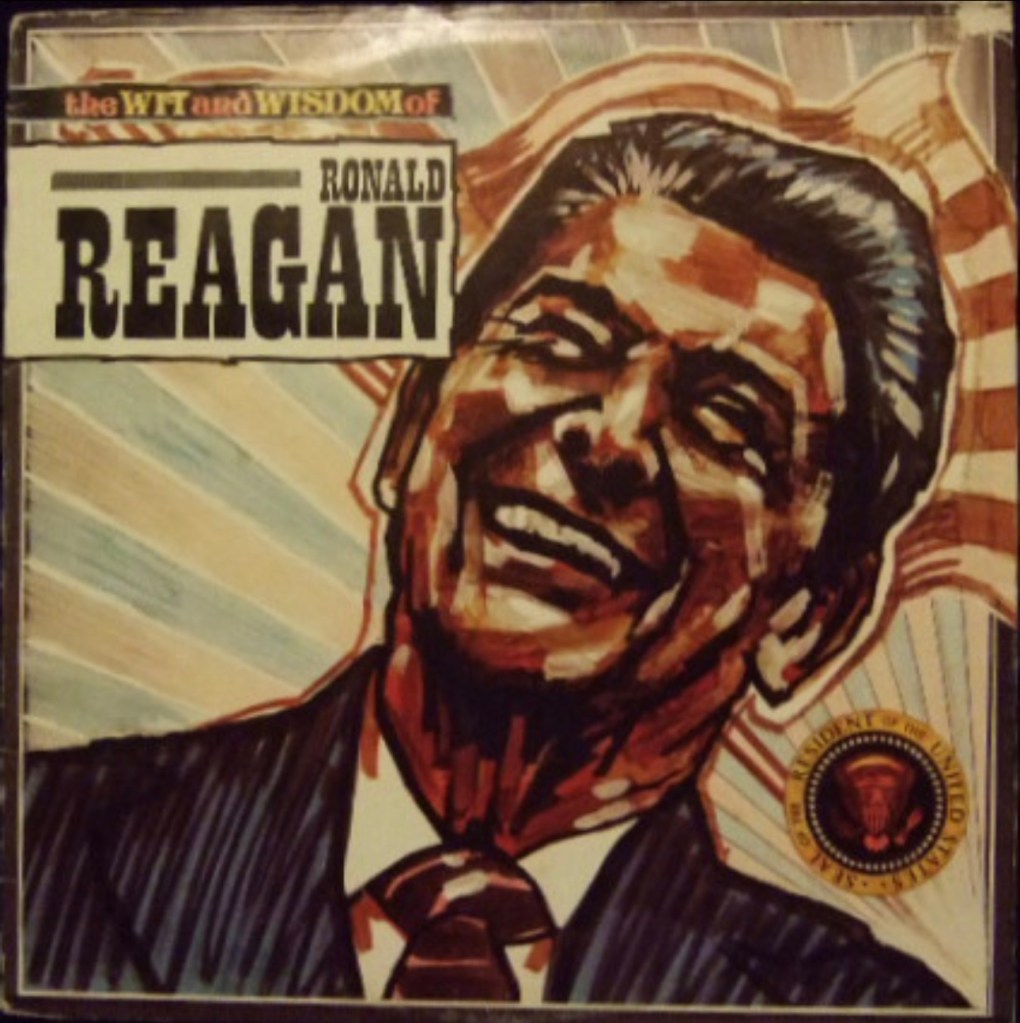

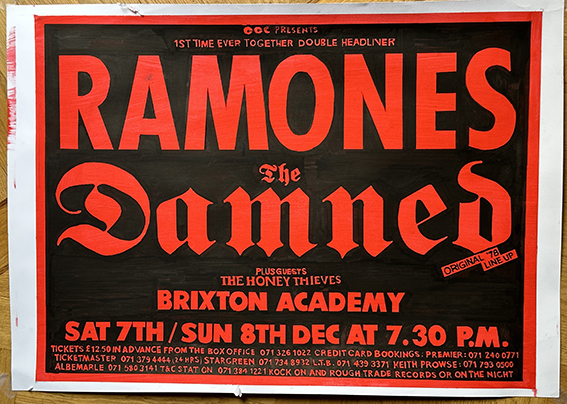

And then there are my paintings of posters and record sleeves.

There is a fine line between appropriation and copyright infringement. Warhol, or the Andy Warhol Foundation, was sued on at least three occasions. The first was in 1966. when Patricia Caulfield (1932-2023) sued Andy Warho for his use of her photograph of hibiscus flowers photographed in a Barbados restaurant as the basis for his series of Flowers paintings and prints. The case was settled out of court with Warhol paying Caulfield $6000 (from the sale of two Flowers paintings plus 25% of the royalties from the sale of the Flowers prints.) Warhol had, apparently, offered to licence the use of the photogeaph from the Modern Photography magazine, but was unwilling to pay the price quoted.

In 2011 the Andy Warhol Foundation intended to licence the use of Warhol’s Banana design for use for ipod and iPad ancillary products. However, the Velvet Underground threatend to sue as the band considered the design “to represent a symbol, truly an icon of them Velvet Undergound”. The matter was settled out of court with the Foundation publishing a letter stating that the matter had been resolved by a confidential settlement.

In 2021 photographer Lynn Goldsmith sued the Andy Warhol Foundation for licencing Warhol’s portrait of Prince to Condé Nast Publishers without credit to Goldsmith. She eventually won in the Supreme Court which decided that the Warhol version of her photograph was not sufficiently “transformative” to justify “fair use”, a legal term used to exempt use of copyright materal without having to pay the creator. Such use could be in reviews, criticisms or similar situations.

Other artists, ranging from the above-mentioned Sturtevant, to Jeff Koons, Richard Prince (who also lost a suit over his appropriation of five of Patrik Cariou’s photos of Rastafarians that Prince used in his 2008 exhibition Canal Zone at the Gagosian Gallery), and most recently, Eric Doeringer who makes “bootlegs” of other artists works, including Richard Prince’s! Apparently Prince has given Doeringer his blessing but Takashi Murakami was not so impressed with Doeringer’s work and issued a “stop and desist” order to prevent him from using Murakami’s work.

I have three examples of Richard Prince’s work in my collection: his 12-inch, limited edition , single sided vinyl Loud Song (with cover art by Sonic Youth’s Kim Gordon), a 7-inch flexidisc of Loud Song that is included in his High Times! monograph published by Gagosian, and the limited edition, picture disc It’s a Free Concert Now. I recently saw that Eric Doeringer has made a 7-inch version of Loud Song with two other songs (Catherine and My Way) and made a new version of Kim Gordon’s cover art. This EP has been pressed in a limited edition of just twenty-six copies, numbered from A to Z. I got number J.

Doeringer (born 1974) has achieved serious acceptance for his art by being awarded gallery exhibitions and thus a degree of fame. I find his story encouraging and a stimulus for my own continuing appropriation of other artists’/designers’ work. Hopefully my works will be suffiently “transformative” to be considered “fair use”.

There is a lot more to be said about appropriation art. There are several artists reproducing record covers commercially that could possible fall foul of copyright law. So far, though, they do not appear to have been challenged.